ROOTS OF THE GRAND OLD BREED – By Richard F. Stratton

ROOTS OF THE GRAND OLD BREED – By Richard F. Stratton

Without a doubt, the American PitBull Terrier is the most controversial breed in the world today. It wasn’t always thus. Only forty years ago, it was but a little known breed, and the people who

did know about it often had misconceptions. Now the breed is so famous that its name is part of the lexicon, and rock groups are even named after it. And not only do misconceptions still abound, but it is becoming difficult to distinguish the true-breed from pretenders.

How could such a thing happen? Well, the old quote by John Taintor Foote is still true, “Make him whatever color you like, civilize him as you please, and man will still worship the born fighter.” This seems to be true, and by “man” he meant humankind, as women are equally enthralled by such things. I have always been to some extent puzzled by this, for scientists have shown that we humans are the most cooperative of all the primates and the least given to outbursts. That has been our edge, that and superior intelligence—but intelligent people or “wonks” or “geeks” don’t draw the admiration that is garnered by the warrior types.

The popularity of the breed is often dismissed as myth by those who go by registration figures, and that’s because many breed members aren’t registered, and those that are often have different breed names in different registries. I used to love the breed because of the fact that it was the gladiator par excellence of dogs, and I still like that, as well as their freaky athleticism. But I have come to love the Bulldog character, too. For such a fearsome breed, they are such good guys with people, and their dispositions are dependable. Besides that, they are as smart as any breed, and I think, with prejudice, that they are a little smarter.

My point here now is to tell about the roots of the breed, and here, I mean “recent roots.” I should have made that the title, but it didn’t sound as good. No one knows the true roots of the breed, but convincing evidence from artwork four hundred years old, and older, indicates that they were first used as kill dogs in hunting large, rough game. It was probably not long after that their owners pitted them against each other, just to see who had the better fighter, but there is no hard evidence of that. Certainly, they were used for fighting long before bull baiting was outlawed, and I doubt that such an activity was ever very widespread anyway.

In referring to recent roots, I am talking about the oldtime dog men of the 19th century. I normally prefer to emphasize dogs over the people, but here I’ll give some of the fanciers a little appreciation. One of the best known was John P. Colby. All of our dogs trace back to at least some Colby dogs. As for Colby himself, he had a short and happy life. He loved race horses, racing pigeons, and game chickens. But he loved Bulldogs most of all. I was a guest of his son, Louis B. Colby, back in 1999, when I was 68, and Louis was 78. We had previously had a correspondence when I bought a pup from him when I was 16, and he was 26. We hit it off immediately when we finally met in person. Why should we not? I was very much interested in the father that he so much admired. And he apparently attracted admirers in his own time, too. He was frequently pictured with famous figures of the times, and he had bought some property that was ill suited for the dogs, so he rented it out yearly to Buffalo Bill Cody!

Lou showed me the very original picture of Colby’s Pincher in a gilded frame. All the other pictures printed in books and publications around the world came from that particular picture because he lived, after all, in the 19th century. I was amused when Lou told me all the family’s pictures in the house were actually pictures of dogs that they were posing with! John P. Colby had his family in a large house, and he bought another large house across the alley, where he housed his dogs and birds. That, apparently, was his solution for keeping his animals in the cold New England winters. Lou took me to the original family house, but the one that had housed the dogs had been torn down. His father used to write the breeding of dogs on the woodwork of the gigantic

“doghouse,” and Lou had saved some of those. I would love to have had some of them as souvenirs, but even I was not so bold as to hint at such a thing.

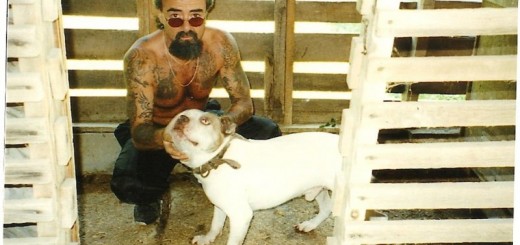

John Pritchard Colby with his “red and white” Paddy

When the elder Colby died peacefully in his sleep, his widow eventually married another dog man, a Colby admirer, who just happened to be a professional astronomer. Lou remarked that it was quite a change for his mother, from his father who, however bright, only went through elementary school. But the Colbys continued to work for the breed. (Obviously, Mrs. Colby now had a new name, but I’ve forgotten it.) And they were even instrumental in getting the breed officially recognized by the American Kennel Club, something that I might question today, in hindsight. But there were others before Colby, believe it or not, and there have been some since that were instrumental in producing the dogs we have today—that are not too much different from what they had back then! Colby was especially important because he sold dogs to the general public. He was able to get by with that without drawing derision from other dog men, a rarity even then. In the final analysis, though, people that sold dogs to at least other dog men are the ones who had the most influence on the breed. One of the breeders most admired in his time was James Corcoran, a Boston police captain. His dogs were considered among the best, and they were Old Family dogs that he had imported from Ireland. It is interesting to consider, in retrospect, how many good dogs came from Ireland. Good racing horses and game chickens also came from the Emerald Isle. William J. Lightner was in his 80s when I first met him in the 40s, and he still kept dogs that were in much demand.

His wife was still alive then, and she took care of the correspondence and the paper work on the dogs. Like the Colbys, they registered their dogs with the United Kennel Club and the American Dog Breeders Association. Lightner had done many things throughout a long life time. He was a big man and used to sing in bars, but he also was a successful bare knuckle boxer—and he was a life-long railroad man. One reason the Lightner dogs were so esteemed was the incredible gameness of the dogs, and there were two Lightner strains. The first one was part of the foundation for the Old Family Red Nose strain. In his old age, Lightner liked them small, and he came up with a line of small dogs that also produced incredibly game individuals, such as Colorado Dan and Imp. Those dogs are way back in many a modern pedigree. How far the original strain went back was hard to say, but Mr. Lightner told me that his father and his uncle put the strain together back before the Civil War. When I was a boy, I got the Armitage book from George Armitage himself. It cost four dollars, and it had a green paper cover. I remember my father making a derogatory comment about a paper-covered book that cost four dollars. This was back in the days when you could get a hard bound book for only one or two dollars. In fact, some series came two for a dollar! In any case, it was like gold to me. In retrospect, I have many criticisms of the book, and unfortunately, someone has kept this privately published book going, and it can be bought on line.

I asked Lightner about the book, and he told me that George was known to have had some pretty good dogs, but he ruined his book by vilifying good dog men, such as Redican and MacDonald. I read the book many times, and I could see that Redican dogs became Armitage dogs when they won for him, but when they lost, they were “Redican” dogs. One lost against Cincinnati Paddy, but he lost game, and Paddy was on Armitage’s three greatest dogs list, so it does seem as though he was a little unfair. Mike Redican was a good dog man who produced and sold many good dogs. Harry Clark was also mentioned by Armitage, but he didn’t say anything against him. I suspect Clark was a better dog man than Armitage. Billy Sunday was considered one of the greatest dogs of all time, and he was listed as the best he ever saw by Clark, and Clark owned Kager after Armitage (changing his name to Tramp) that Armitage had called the greatest. I guess Armitage didn’t list Billy Sunday because he lost to him. Dan McCoy was not a breeder himself, but he was a respected dog man. He couldn’t keep dogs himself because he was an itinerant fry cook for oil companies and he traveled all over the country.

But he knew where the dog people were, and he was a great judge of dogs, and he had a photographic mind for pedigrees. Because of all of that, he engineered some great breedings as an advisor to other people. According to Hemphill, he was the one who first started calling the Old Family Red Nose dogs by that name. D. A. Mc- Clintock was one of the great breeders of that strain, and he recruited his nephew Howard M. Hadley to the breed. Tudor is one of the best known old timers today, but he really wasn’t that much of a breeder, as he paid no attention to pedigrees. Nevertheless, he bred some good ones, just because he had so many good dogs go through his yard. In addition, he had the advantage of being friends with a sheriff, Jim Williams, who was a great breeder and a source of some great dogs. Tudor was a great judge of dogs, and he influenced a lot of people, and that’s one reason he is still so well known.

I think one of the great dog men was Bob Wallace, but he didn’t let many dogs out, so he didn’t influence the building or furtherance of quality dogs because of that simple trait. Bob Hemphill had some of the same bloodlines, and his dogs show up more in pedigrees than Wallace’s, as he was willing to sell dogs. When he went into the hospital for a serious illness, Jake Wilder, a former Redbone Coonhound devotee, used his kennels to take Bob’s dogs. Bob never left the hospital, so his dogs come down to us mainly through Wilder. Even though Wilder was relatively new to the breed, he wrote a popular column for Bloodlines Journal, and I had occasional correspondence with him. Joe Corvino and Con Feeley were active in Chicago. The Corvino dogs became more numerous because Corvino also sold dogs to the general public, and he registered them in all three registries: ADBA, the UKC, and the AKC. Jack Williams rented a rooming house above Con

Feeley’s saloon, and Jack was responsible for preserving the Feeley line and getting it into the hands of other breeders.

Al Brown was an influential breeder whose Tacoma Jack dog became the foundation dog for Charles Doyle’s Tacoma Kennels, which were later known as winners in dog shows as Stafs. Doyle was one of the few people who bred dogs for both the pit and the show ring. In the early 50s, I met Maurice Carver. He was a young dog man then, but he was a handsome fellow, and he had a pleasant personality—and he had already developed a good eye for dogs. I remember Bob Hemphill encouraging him to breed dogs, and he replied that he didn’t have the patience for them to grow up. But he later became one of the most influential of all breeders, as he sold good dogs at fair prices. However, a lot of those weren’t Carver dogs. He was something of a dog broker. He knew where the good dogs were, and he could pick them up and sell them for twice as much.

He didn’t necessarily fake pedigrees; he just didn’t give them out. There are so many great dog men that it is difficult to say a lot about all of them, but I wanted to mention some of the early ones. I have intentionally left out those of my generation, as I couldn’t possibly cover them all. I have only mentioned early dog men, and I didn’t go back as far as I should, and I have unintentionally left some out. But I wanted to give a sense of the dedication dog men had for this breed before it became famous—or notorious, as unfortunately it is today. Even in the old days , this great old breed had a touch of infamy to it because its appeal was often to a thuggish element, then just as it is now. I take comfort in the fact that really knowledgeable dog people, from trainers to scientists, appreciate the quality of this noble breed, and they have worked as keepers of the flame.