HANDLING YOUR DOG – Jack Kelly

In the just recently passed several decades, just about everything about Bulldogs have improved tremendously. New medications have helped us save pups, and young dogs that might otherwise

have died. Just consider that it wasn’t very long ago that getting rid of something like tape worms was usually a job best done by a veterinarian. Two days of fasting and physicking to accomplish

what one cc of the drug Droncet does, and does it much better, and all the time it takes is the time to load up a syringe. The techniques for saving a dog after a long hard performance have saved untold numbers of dogs that would have otherwise died of their injuries. Commercial dog foods have kept dogs healthier longer, and lengthened their reproductive years. Canine nutrition has improved to the point where just about every serious conditioner knows how, what and when to feed his dog to bring him or her to their peek. Exercise technology has taught us the best exercise for dogs, and how to effectively use it to increase a dog’s strength, and stamina. There is really only one aspect of the dogs that have not only NOT improved, but has taken a definite slide backwards…

I think we can all agree that the job of a handler was to do everything possible, within the rules, to help your dog win. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to let go of your dog when the referee calls, “Release Your Dogs”. It’s shortly after this that the problems started, and gets worse as the match progressed. The first bit of thinking that the handler had to focus on was the “Turn”. We

all know what a turn is, it’s when a dog turns his head and shoulders away from the other dog. It has always, since the beginning of time, been considered a bad move. The whole concept of a turn roughly parallels a knock down, in the old Marquis of Queensberry, bare knuckle boxing matches.

If a boxer was knocked down, he was helped to his corner, where his handlers had a minute to help him recover and regain his senses, walk out to the scratch line in the center of the ring, and assume an aggressive posture to indicate, to one and all, that he is ready, able, and willing to continue the contest. It was called “Coming Up to Scratch”. A dog can’t get knocked down, but if he turns away from his opponent, then he must come up to scratch. Since you can’t teach a dog to just simply go to the center of the pit, and growl at the other dog, he was required to go from his corner to his opponent corner and take a hold. The match, and the boxing match, then continues until the dog, or the man, will not, or can not “Come up to Scratch”, or his handlers concede.

Back to the match. Either handler could petition the referee to allow a turn on either dog. It is then up to the referee to determine whether or not the dog had, in his opinion, actually committed a turn. If the referee allows the turn he would then instruct the handlers to handle their dogs when they were free of hold. The referee should not hold some sort of a mini conference with the handlers to try and get everyone to agree that a turn has actually been committed. It is the referee’s call. In many instances, once a turn was allowed, both handlers would hover over their dogs anxiously waiting for the slightest indication that the dogs may be close to coming out of hold. Apparently, it would appear, that no thought was given to the fact that it might not be in the best interest for one or the other dog to be handled. Certainly, if your dog had committed the turn you might what to get a quick handle, to have your dog scratch as soon as possible. If on the other hand your dog has just kicked it into high gear, and is on top going strong, then you surely don’t want a quick handle. The rules require that you must handle your dog when both dogs are out of

hold, but that doesn’t mean that you cannot encourage your dog to stay in hold, if that is too his advantage. It usually appears that both handlers were so intent on getting the dogs scratching, that they gave little or no thought to the proper strategy that would be the most advantageous for their dog. It actually appeared that neither handler had any kind of preconceived plan of what he was doing.

After a few handles the anxiety really starts to show on both handlers, and by now they are attempting to handle while the dogs are still in hold. In many cases this can get pretty rough on the dogs. For example: The BUCK + SANDMAN match. I was standing, perhaps a foot away from the pit. Ricky Jones attempted to handle SANDMAN while his dog was underneath BUCK, who had a soft hold on SANDMAN. Ricky reached down, grabbed SANDMAN high on his stifles, and snatched his dog right out of BUCK’s mouth. In so doing, he swung the his dog high in the air, in

a big arc. Some part of his dog, probably a front leg, grazed my head, and knocked the hat off of my head. Ricky’s backers, among the spectators, applauded with cries of, “Nice handle Ricky”. Imagine if you will, this maneuver from the dog’s point of view. He’s down there, swapping it out with the other dog, at somewhere around an Hour and a half into the match, when suddenly he finds himself flying through the air, and then bounced around in his handler’s mad dash to get to his corner, where he is placed down and almost drowned with water. It’s amazing that it doesn’t take more than 25 seconds for a dog to recover from that kind of handling. The whole procedure, in all probability, did more harm to SANDMAN than what BUCK was able to do at that stage of the contest. Gently does it, and I’ll never know why some handlers feel it necessary to get back to their corner as soon as possible. The referee can not start counting until both handlers are comfortably back in their respective corners.

There are a hundred little things that a handler could do to help his dog win. A dog is basically color blind. Your about an hour into a tough match. Your dog has to be somewhat disoriented, and he’s up to scratch. The referee says, face your dog, and you turn and point him in the right direction, and he looks across to where the other dog is standing. The other handler is holding a white dog, and wearing black pants, I guarantee that your dog is going to see that contrast a whole lot sooner than he would if the handler was wearing a light colored pair of pants. Several years ago, my friend Don Colbert was matched into Jimmy Space Cowboy, and a bitch called DOE that came from Sorrells. Colbert’s bitch was as cross eyed as that old time comedian that used to appear in many of the Laurel and Hardy movies. I think he made a good living just being able to make himself look cross eyed.

The cross eyed bitch wrecked DOE for about 15 minutes, and DOE tuned and ran a good scratch A quick handle, and it was the cross eyed bitch’s turn to scratch. DOE was a buckskin bitch and Jimmy was wearing khaki colored pants. Colbert pointed his bitch in the right direction, of course, he was only guessing, you could never tell where the bitch was looking. Jimmy and DOE stood absolutely still in their corner, and I’m sure the cross eyed bitch never saw more than a light colored shadow. She took a couple of tentative steps out of her corner, and at about that time, a spectator, sitting about half way between DOE’S corner, and a neutral corner, stretched his arms up over his head. The cross eyed bitch scratched, straight and true, right to that movement. Of course, there was no dog there, and cross eye looked all around and couldn’t find Doe until the referee said “Ten”. If Jimmy had made DOE an easier target, and didn’t keep DOE as still as he did, it might have turned out differently.

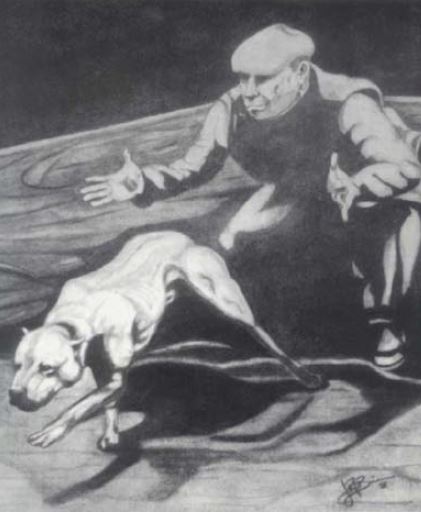

Handling a dog in a show is probably the most neglected aspect of what is important to help your dog win. Some handlers seem to just have a knack for doing the right thing at the right time, while other handlers seem to do the wrong thing at the wrong time. I refereed a match in New England many years ago, in which the handler actually snatched defeat from the hands of victory. I don’t remember this handler’s name, he was a new fellow, probably handling a dog for the first time. He was matched into Irish Al Kivlin, and his champion dog SPIKE, a veteran of three contracted

wins, several off the chain wins, and many rolls, He was pushing seven years of age. Al thought he could win one more time. The newcomer was handling a big, strong, young black dog, that looked like he wanted to eat SPIKE for lunch, and he was doing just that for almost an hour when SPIKE turned. The old dog looked like he didn’t want to scratch, he was feeling his age, and that young black dog was all over him. Then I looked over to the other corner. The newcomer was holding his dog with one hand, and had a fist full of skin on the back of the black dog’s neck, and sticking his arm, full length, out of his corner. The black dog looked like a puppet on a string, dancing around trying to get loose so he could get back to the action. You could almost see what was going on in SPIKE’s mind, when he saw all that movement he figured he could try it one more time. SPIKE kept trying it one more time until the black dog decided he had enough, and stayed in his corner.

Something I alluded to previously, putting water on a dog, in your corner, after a handle. The dog naturally is hot from the action, and you want to cool him down. You have 25 seconds to accomplish that. The fastest way to do that is to saturate the dog with water, however, the faster you cool the dog down, the faster he will heat up when exposed to the same thing that got him hot in the first place. It might be the best thing to do if the handles are coming rather frequently, and the dog will have less opportunity to heat up again before the next handle. But, if both dogs are going at full speed ahead, and, you estimate that the next handle might take some time, then you don’t want to use too much water. Put the water where the hair is less dense, along his chest and belly, wet the places where a dog naturally sweats, the pads of his feet and his tongue. He might not cool down as fast, but neither will he heat up again as fast.

Another thing that I have observed over the years that an unthinking handler might do that might cause a problem. When it was that handler’s turn to face his dog, the dog was between the handler’s legs, when the referee called out to “Scratch your Dog”, the handler would take his hands off of the dog and if the dog does not immediately start to scratch, the handler should step over the dog, and not let the dog remain between his legs.. It is entirely possible that the dog feeling your legs on his rib cage, will still think he is being restrained. The handler should be certain that his dog knows that he has been released. The handler cannot step across the scratch line but he can reach over the scratch line to encourage his dog, but make sure he is not still being restrained.